Word Choice

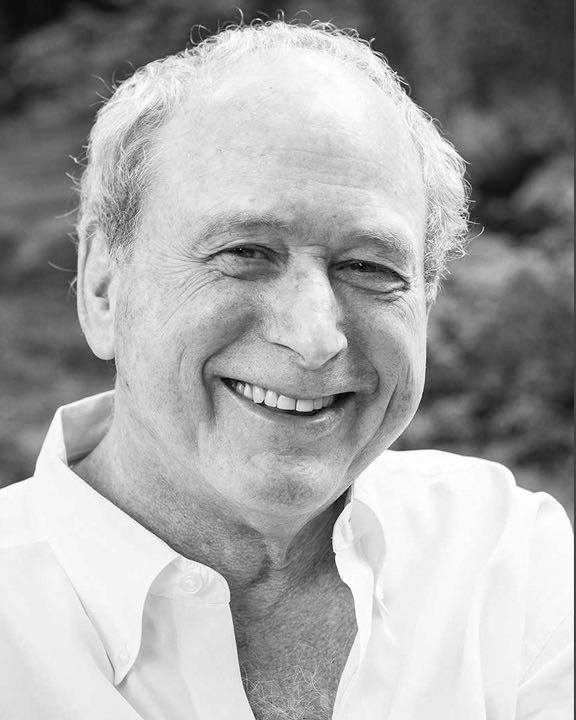

My late husband, Bob, was a hospice and palliative medicine physician. Early in our relationship, as we shared family histories, I told him about my brother David. When David was 13 (I was 18), he was in an accident and remained in a coma for 21 days. For years I had described it the same way: “No brain activity was detected, so my parents had to make the heart-wrenching decision to remove him from life support.”

Bob listened attentively. A short time later, he offered me something I hadn’t considered: “Jen, we don’t call it life support.”

“Life Support” Isn’t Life Support

I had been working in healthcare for decades and had heard countless professionals use the term. Bob explained why it mattered. First, it isn’t accurate. Intubation supports organ systems and physiological functions, not “life” as most people understand it. Second, calling it “life support” makes the decision to extubate unbearably harder. Families feel as though they are choosing to end their loved one’s life, when in fact they are allowing a natural death.

From then on, I used more accurate terms — “intubation,” “organ system support,” or “medical support.”

“Feeding Tube” Isn’t Feeding

The same is true of the phrase “feeding tube.” Please don’t call it that. There is no dining experience. When professionals use that phrase, the cruel consequence is this: if later the family is asked to consider removing the tube, it sounds as though they are being asked to starve their loved one to death.

The device provides nutrition and hydration by medical means, not “feeding” in the way most people understand it. More accurate terms include, “nutrition administration,” “nutrition tube,” or the specific type of device such as “PEG tube.”

The words of healthcare professionals shape how patients and families think and feel. Accurate language can mitigate false hope and misplaced guilt.

Precious Time

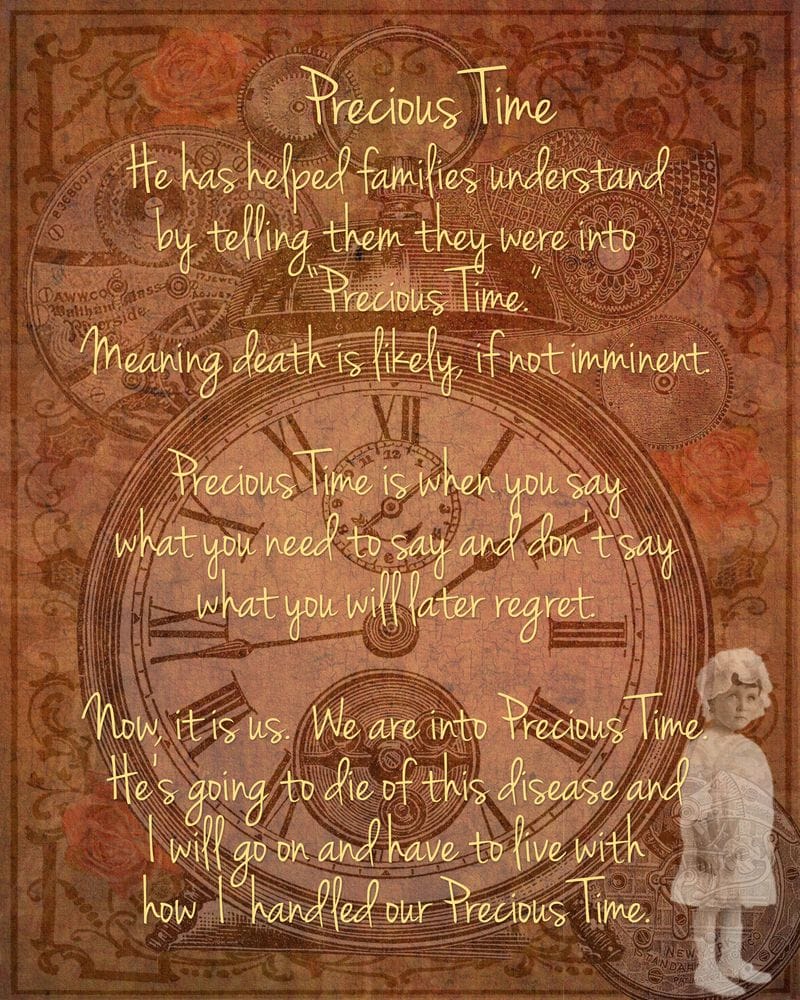

Bob also gave me another phrase. Many evenings, a recap of the day would include him saying, “I told the patient and family, they were into 'Precious Time.' This meant that death was nearing or imminent. The emphasis is always on the first word because this is a distinct period of life, its end. He might further explain to the patient and their family, by sharing that precious time is when you say your "I love yous, I’m sorries, I forgive yous, thank yous, etc."

In my first book, The Hospice Doctor’s Widow: An Art Journal of Caregiving & Grief which was an art journal I created while caring for Bob, I included the page you see at the top of this article.

Precious Time is when loved ones can be fully present, say what needs to be said, and begin laying the foundation for their own survivorship. Not every moment is picture-perfect, but knowing death is near gives loved ones the chance to prevent or minimize regrets. I know that families appreciated Bob telling them death was nearing because he would receive handwritten thank you notes from surviving loved ones.

Precious Time in Practice

I have no regrets from the 22 months Bob was ill, because from diagnosis we knew we were already in Precious Time. Perhaps it was early-onset Precious Time — I don’t recall Bob ever telling a family that nearly two years out — but naming it shaped how we lived it.

Since publishing The Hospice Doctor’s Widow: An Art Journal of Caregiving and Grief in 2020, I’ve been elated to hear from healthcare professionals who now use the term "Precious Time". Many nurses and physicians have followed up with me to say incorporating “Precious Time” into their lexicon has resulted in families coming together before a death of a loved one with time to have a meaningful exchange.

Not everyone gets Precious Time. It is a blessing when we recognize it, name it, and face it.

Carrying the Words Forward

Because of this feedback from clinicians worldwide, I put together the “Precious Time Implementation Guide for Healthcare Professionals” a free download that can make difficult conversations easier.

Bob would be so happy to know that “Precious Time” continues to help clinicians. Please, use the term. Practice it. Role-play it with colleagues. And when the time comes, offer it as the gift it is.

Post-Word by Dr. Carrie Hyde, Palliative Care Physician

I had the profound honor of training with Dr. Bob Lehmberg early in my palliative care career. I witnessed firsthand how he used these very techniques—language that softens fear, reframes decisions, and honors the humanity of patients and families. His approach forever shaped how I practice palliative care.

“Precious Time.”

“Organ system support.”

“Nutrition administration.”

These aren’t just words. They are compassionate tools. Bob taught us that language either burdens or liberates the people we serve. Watching him, I learned how to give families permission to love, to let go, and to live fully in the final chapter. His presence in the room changed everything.

Special thanks to Jennifer—for sharing Bob’s teachings, which I had the opportunity to learn firsthand all those years ago, and for sharing them now with our colleagues around the world. Your voice is extending his legacy even further than he ever could have imagined.

In honor of Dr. Lehmberg’s legacy—and the Precious Time I had learning beside him—I offer my deepest gratitude. His wisdom lives on in every family I counsel, every word I choose, and every moment I help protect. May we all continue to carry his language, his heart, and his courage into our work.